Ultimately, then, when photographs are uncritically presented as historical documents, they are transformed into aesthetic objects. Accordingly, the pretence to historical understanding remains although that understanding has been replaced by aesthetic experience

(Sekula, 1991, p.123)

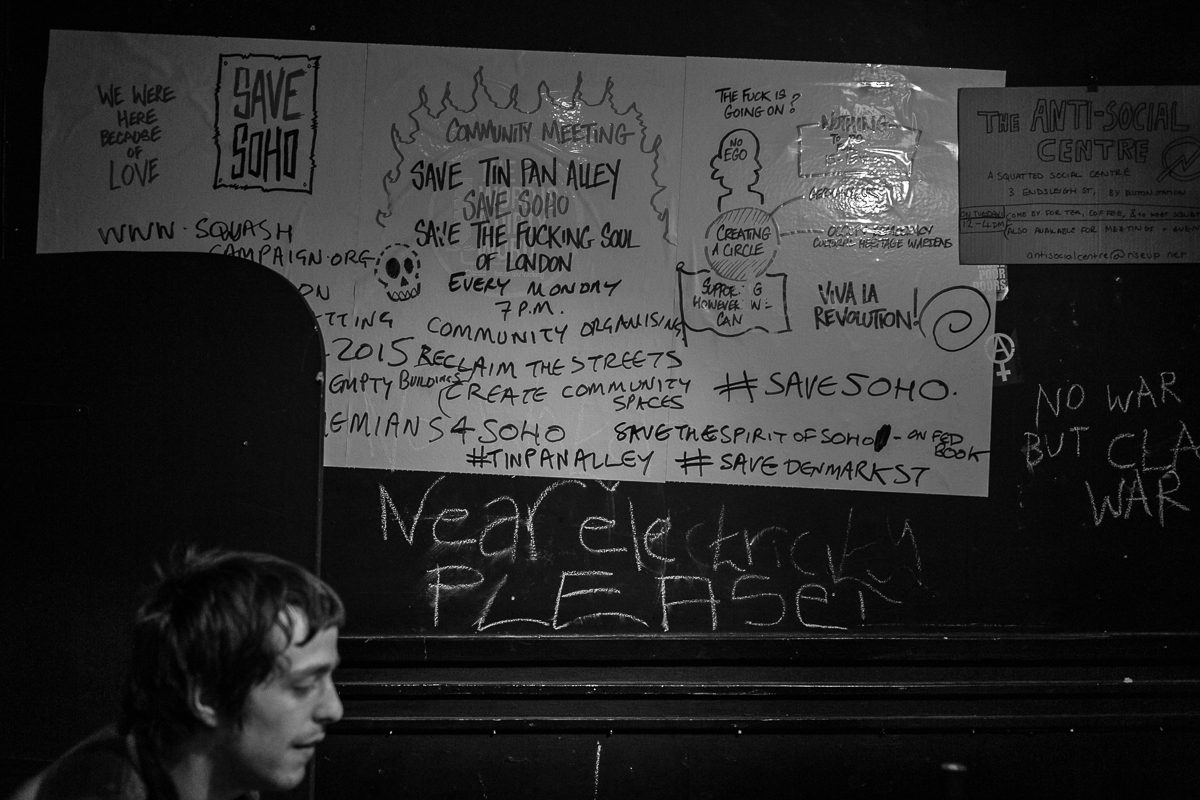

The quote above is part of a critical debate about documentary photography and one which we were asked to think about when we went round the Conflict, Time, Photography exhibition at Tate Modern a couple of weeks ago when the class went together.

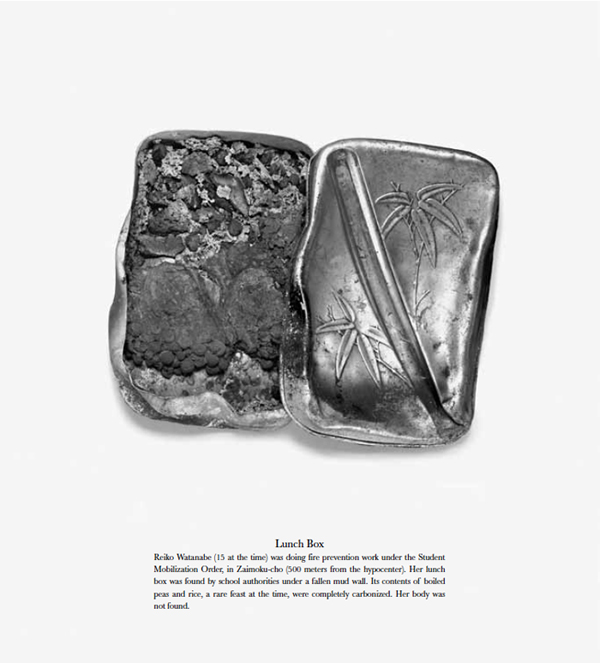

Yesterday, I visited again, starting from the middle of the exhibition where I finished off last. There were a couple of series of photos that really stood out for me, which have the 'punctum'. One particular series was Hiromi Tsuchida's Hiroshima collection 1982-95. He photographed articles from the collection at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum 37 years after the event. These photos included text which gave a short description of the object and their owners. The physical photo of which they were printed in the gallery context was slightly bigger than A0 size and were gelatine silver print on paper.

Hiromi Tsuchida

Hiroshima collection 1982-95

Hiromi Tsuchida

Hiroshima collection 1982-95

Due to the physical size of the print, I found the jacket image quite powerful as it was about human size printed and the imagination of what happened whilst you read the description is one that gripped me.

Hiromi Tsuchida

Hiroshima collection 1982-95

Hiromi Tsuchida

Hiroshima collection 1982-95

In the accompanying text right next to the prints, it described the photos like 'a form of posthumous portraiture'. For me, the sense of calm of the simple images plays with the direct opposite of the historical event, one which we can only imagine. This really brings us back to the Sekula quote above.

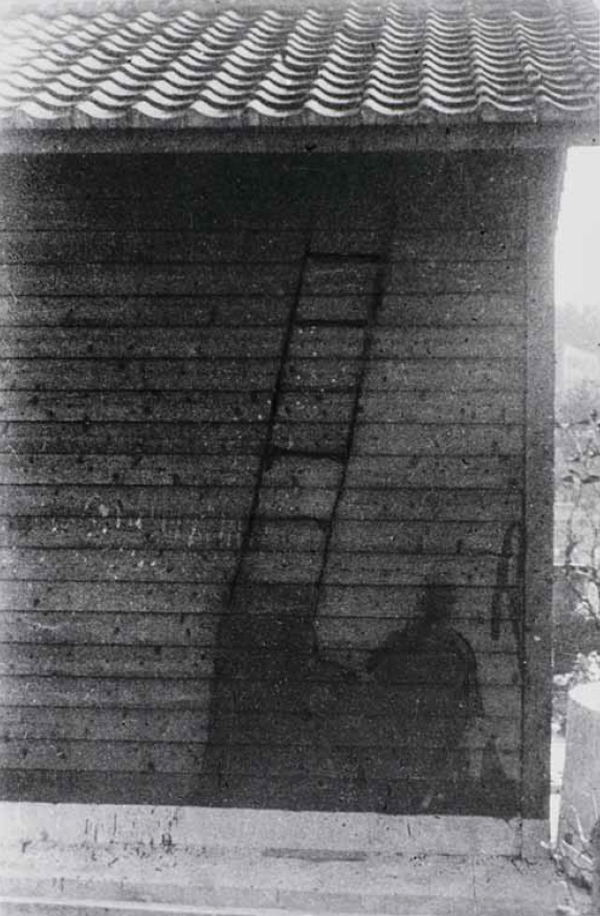

Interesting enough, during my first visit, I chose the following photo, Shadow of a soldier remaining on the wooden wall of the Nagasaki military headquarters (Minami-Yamate macho, 4.5km from Ground Zero) by Matsumoto Eiichi as the photo which had the 'punctum'. This photo was taken approximately three weeks after the atomic bomb exploded over Nagasaki.

Shadow of a soldier remaining on the wooden wall of the Nagasaki military headquarters (1945) by Matsumoto Eiichi

Shadow of a soldier remaining on the wooden wall of the Nagasaki military headquarters (1945) by Matsumoto Eiichi

The photo affected me personally as what I had initially thought was a shadow were actually caused by the heat of the bomb and as these humans and objects was exposed to the blast, 'the intensity of the explosion had created 'burned in' shadows'. This image as compared to Tsuchida's Hiroshima collection documents the remains of a Japanese guard in its context. The gelatine silver print on paper image is roughly A4 size (315mm x 207mm) and much smaller compared to Tsuchida's images. It is very interesting to compare how these images were made at different times after the event and how both of them affected the viewer (i.e. me) differently.

One other series of photos taken 99 years after the event which stood out for me was Shot at Dawn by Chloe Dewe Mathews.

Shot at Dawn by Chloe Dewe Mathews

Shot at Dawn by Chloe Dewe Mathews

The images were the locations where WW1 British, French and Belgian soldiers accused of cowardice and desertion on the western front were executed. She 'took the images at the exact time at which the executions took place and as close as possible to the actual date'. If you looked purely at the images without reading the accompanying text next to the exhibited images, you see a landscape photograph. Once you read the accompanying text which states the names of the people executed there, the time and date of execution and the location, the viewer starts to see more in the image through the 'evidence' of the text.

Following the exhibition, I checked out the video where Chloe De Mathews talked about this body of work. She mentioned about the relationship of the text and the image which is like 'stamping the presence of the person back into the empty landscape', the point she is trying to make. It is the 'absence that is glaringly present'.

It is such an interesting exhibition and one where you need time to slowly digest and understand the different approaches the different photographers and artists choose to represent conflict.